Introduction

On Good Friday, we continue our meditation on the meaning of Passover. In so doing, we discover that Jesus himself is our Passover.

Three different faces of Jesus are offered for our reflection: the prophetic Suffering Servant, the great high priest, and the triumphant king. We end our meditation with reflection on the power of the cross.

1st Reading – Isaiah 52:13-53:12

See, my servant shall prosper,

he shall be raised high and greatly exalted.

Even as many were amazed at him—

so marred was his look beyond human semblance

and his appearance beyond that of the sons of man—

so shall he startle many nations,

because of him kings shall stand speechless;

for those who have not been told shall see,

those who have not heard shall ponder it.

Who would believe what we have heard?

To whom has the arm of the LORD been revealed?

He grew up like a sapling before him,

like a shoot from the parched earth;

there was in him no stately bearing to make us look at him,

nor appearance that would attract us to him.

He was spurned and avoided by people,

a man of suffering, accustomed to infirmity,

one of those from whom people hide their faces,

spurned, and we held him in no esteem.

Yet it was our infirmities that he bore,

our sufferings that he endured,

while we thought of him as stricken,

as one smitten by God and afflicted.

But he was pierced for our offenses,

crushed for our sins;

upon him was the chastisement that makes us whole,

by his stripes we were healed.

We had all gone astray like sheep,

each following his own way;

but the LORD laid upon him

the guilt of us all.

Though he was harshly treated, he submitted

and opened not his mouth;

like a lamb led to the slaughter

or a sheep before the shearers,

he was silent and opened not his mouth.

Oppressed and condemned, he was taken away,

and who would have thought any more of his destiny?

When he was cut off from the land of the living,

and smitten for the sin of his people,

a grave was assigned him among the wicked

and a burial place with evildoers,

though he had done no wrong

nor spoken any falsehood.

But the LORD was pleased

to crush him in infirmity.

If he gives his life as an offering for sin,

he shall see his descendants in a long life,

and the will of the LORD shall be accomplished through him.

Because of his affliction

he shall see the light in fullness of days;

through his suffering, my servant shall justify many,

and their guilt he shall bear.

Therefore I will give him his portion among the great,

and he shall divide the spoils with the mighty,

because he surrendered himself to death

and was counted among the wicked;

and he shall take away the sins of many,

and win pardon for their offenses.

The Book of Isaiah is considered by many to be the zenith of Hebrew poetry, with this reading, the fourth Servant Song, its doubtless pinnacle.

In this passage, an account of the afflictions of a righteous man (i.e., the suffering servant) is framed by two utterances of God. This portrait of innocent suffering challenges the traditionally held conviction that misfortune is evidence of sinfulness. Framing this unconventional theological position with God’s words serves to legitimize this profound insight.

Most probably Isaiah intended the servent to represent the people of Israel, particularly those who had suffered the exile, and yet who continued to trust that God would one day vindicate their faithfulness. From the very beginning of Christianity, Christian tradition recognized in the Servant Song an evocative prophecy of Jesus’ passion, death, and resurrection.

See, my servant shall prosper, he shall be raised high and greatly exalted. Even as many were amazed at him — so marred was his look beyond human semblance and his appearance beyond that of the sons of man — so shall he startle many nations, because of him kings shall stand speechless; for those who have not been told shall see, those who have not heard shall ponder it.

The poem is comprised of three stanzas. In the first stanza, God speaks, providing a kind of overture to what follows.

God does not suggest the servant’s exaltation is reward for his humiliation; rather, it is precisely in his humiliation that he is exalted. He is raised up even as the bystanders are aghast at his appearance.

Who would believe what we have heard? To whom has the arm of the LORD been revealed?

The perspective shifts with the second stanza. It is spoken in the first person plural, narrated by those who have been granted salvation through his tribulations.

It begins with an exclamation of total amazement. Who would have ever thought that the power of God (“the arm of the Lord”) would be revealed in weakness and humiliation?

He grew up like a sapling before him, like a shoot from the parched earth; there was in him no stately bearing to make us look at him, nor appearance that would attract us to him. He was spurned and avoided by people, a man of suffering, accustomed to infirmity, one of those from whom people hide their faces, spurned, and we held him in no esteem.

The details of the servant’s humiliation are now sketched. Unlike many righteous individuals whose lives contain episodes of misfortune, this servant lived a life marked by tribulation from beginning to end. Added to his physical distress was rejection by a community that held him in no regard.

Yet it was our infirmities that he bore, our sufferings that he endured, while we thought of him as stricken, as one smitten by God and afflicted. But he was pierced for our offenses, crushed for our sins; upon him was the chastisement that makes us whole, by his stripes we were healed. We had all gone astray like sheep, each following his own way; but the LORD laid upon him the guilt of us all.

The account is interrupted by the revelation that all this suffering is atonement for the sins of others. The narrator confesses his personal guilt and acknowledges the servant’s sinlessness. Note how the narrator moves from a traditional understanding (“we thought of him as stricken”) to a new, astonishing, insight (“he was pierced for our offenses”).

This startling realization contains two important points: 1) innocent people suffer for reasons that have nothing to do with their own behavior, and 2) the suffering of one can be the source of redemption for another. Prior to this writing, the idea of “vicarious expiation” was unknown in the Bible.

Though he was harshly treated, he submitted and opened not his mouth; like a lamb led to the slaughter or a sheep before the shearers, he was silent and opened not his mouth. Oppressed and condemned, he was taken away, and who would have thought any more of his destiny?

The account of the servant’s suffering continues, with a clear portrayal of his non-violent attitude. He did not retaliate; he did not even defend himself. In fact, he willingly handed himself over to those who afflicted him.

The image of a lamb led to slaughter suggests that the servant knew that he would die at the hands of his persecutors. Still, he chose to be defenseless.

When he was cut off from the land of the living, and smitten for the sin of his people, a grave was assigned him among the wicked and a burial place with evildoers, though he had done no wrong nor spoken any falsehood.

Even in death he was shamed, buried with the wicked.

But the LORD was pleased to crush him in infirmity.

Other translations have “Yet it was the will of the Lord to bruise him; he has put him to grief.”

If he gives his life as an offering for sin, he shall see his descendants in a long life, and the will of the LORD shall be accomplished through him. Because of his affliction he shall see the light in fullness of days;

The text seems to imply that, like the patriarchs of old, the servant will have many offspring, a long life, and be a man of great wisdom. The servant will eventually “see the light in fullness of days” — that is, enjoy happiness and an abundance of spiritual graces.

There was nothing in the servant’s appalling life or death that served as a clue to the significance of this suffering, or its redemptive value, or the source of exaltation it would become. God’s ways are astounding.

through his suffering, my servant shall justify many, and their guilt he shall bear. Therefore I will give him his portion among the great, and he shall divide the spoils with the mighty,

In the third stanza, God speaks again, acknowledging that his servant’s sacrifice is truly efficacious.

because he surrendered himself to death and was counted among the wicked; and he shall take away the sins of many, and win pardon for their offenses.

The will of God is accomplished in the servant’s willingness to bear his afflictions at the hands of, and for the sake of, others.

“The Prophet [Isaiah], who has rightly been called “the Fifth Evangelist,” presents in this Song an image of the sufferings of the Servant with a realism as acute as if he were seeing them with his own eyes: the eyes of the body and of the spirit. […] The Song of the Suffering Servant contains a description in which it is possible, in a certain sense, to identify the stages of Christ’s Passion in their various details: the arrest, the humiliation, the blows, the spitting, the contempt for the prisoner, the unjust sentence, and then the scourging, the crowning with thorns and the mocking, the carrying of the Cross, the crucifixion and the agony” (Saint Pope John Paul II, Salvifici Doloris, 17).

2nd Reading – Hebrews 4:14-16; 5:7-9

Brothers and sisters:

Since we have a great high priest who has passed through the heavens,

Jesus, the Son of God,

let us hold fast to our confession.

For we do not have a high priest

who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses,

but one who has similarly been tested in every way,

yet without sin.

So let us confidently approach the throne of grace

to receive mercy and to find grace for timely help.

In the days when Christ was in the flesh,

he offered prayers and supplications with loud cries and tears

to the one who was able to save him from death,

and he was heard because of his reverence.

Son though he was, he learned obedience from what he suffered;

and when he was made perfect,

he became the source of eternal salvation for all who obey him.

Passersby and onlookers at Golgotha would never have interpreted Jesus’ crucifixion as a sacrifice; for them, the event was merely the execution of just another criminal condemned to die a slave’s opprobrious death. However, in light of the resurrection, Christian tradition did not hesitate to interpret Jesus’ death not only as a sacrifice but a sacrifice so rich in meaning that it stretched traditional images of sacrifice beyond their limits.

Just as our gospel reading from John paradoxically merges suffering and glory into a sublime unity, the author of Hebrews presents Jesus as both sacrificial victim and sacrificer.

Brothers and sisters: Since we have a great high priest

This is the only place in the Letter to the Hebrews where Jesus is designated a “great” high priest: an indication of his superiority over the Jewish high priest.

who has passed through the heavens,

In Jewish liturgical tradition, only once a year, on the Day of Atonement, could the high priest enter the Holy of Holies in the temple at Jerusalem to offer expiation for Israel’s sins.

Just as the high priest passed through the veil to enter into the Holy of Holies, so Christ passed through the heavens into the presence of God. Here, the author sees in Jesus’ offering of himself in obedience unto death the perfect sacrifice that makes him the high priest who can now enter, not the Holy of Holies once a year, but the very presence of God for all time.

As a result, the risen Christ is the high priest who can intercede for us as no other priest ever could. Only God’s life-giving power could transform the public execution of a man into the perfect realization of Israel’s holiest liturgy.

Jesus, the Son of God,

In addition to being the great high priest, Jesus is the Son of God.

let us hold fast to our confession.

The confession being referenced is that of “Jesus is Lord” (Romans 10:9, 1 Corinthians 12:3). The basis of constancy in this confession is the identity of Jesus. As the Son of God, his sacrifice far exceeds anything that the high priest’s ritual could have hoped to accomplish.

For we do not have a high priest who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses, but one who has similarly been tested in every way, yet without sin.

Jesus’ exalted status (great high priest, Son of God) has not distanced him from us. On the contrary, he knows our limitations; as a man, he shared many of them. He was not only tested once, in the desert (Matthew 4:1-11), but throughout his life (Luke 22:28). He was tried to the limit, but he did not succumb to sin.

Jesus had two distinct natures: he was fully human and fully divine. These natures co-existed substantively and in reality in the single person of Jesus Christ. No human can reach across the chasm of sin by his own power; but being one with God, in his divine nature, Christ could and did.

As an authentic human being, Christ carries all the members of the human race with him as he approaches the heavenly throne, and in so doing, he gives us access to God.

So let us confidently approach the throne of grace to receive mercy and to find grace for timely help.

Unlike the Jewish high priests who only approached the mercy seat alone and only on the Day of Atonement, Christ enables us to approach God continually, boldly, and with confidence. There we will receive the grace we need to be faithful.

In the days when Christ was in the flesh,

An allusion to Jesus’ humanity. In the biblical sense of the term, flesh (sárx) is not evil but is fraught with limitations and weaknesses. Because it is subject to deterioration and death, it came to signify many things associated with human frailty, such as vulnerability and fear. For Jesus to have taken on flesh was to have taken on these limitations and weaknesses as well.

he offered prayers and supplications with loud cries and tears to the one who was able to save him from death, and he was heard because of his reverence.

The reference to Jesus’ anguished prayer calls to mind his agony in Gethsemane (Matthew 26:36-46; Mark 14:32-42; Luke 22:40-46). The reference here is probably to a traditional Jewish image of the righteous person’s impassioned prayer. Its sentiments are reminiscent of those found in the psalms that describe agony, terror, and depression (e.g., Psalms 22, 31, 38). Jesus offered these prayers as a priest offers sacrifice, and he was heard because of his reverence, or Godly fear.

Son though he was, he learned obedience from what he suffered; and when he was made perfect, he became the source of eternal salvation for all who obey him.

Though Son of God, Jesus learned what every human has to learn, namely, acceptance of God’s will in the circumstances of life. The surest way to learn this lesson, though perhaps the hardest, is through suffering. This notion points once again to Jesus’ willingness to assume every aspect of human nature. As mediator of salvation, Jesus endured torment of body and anguish of soul. He knew agony, terror, and depression. He could fully understand human distress and the desire to escape it. He was truly one with the human condition.

Gospel – John 18:1-19:42

Jesus went out with his disciples across the Kidron valley

to where there was a garden,

into which he and his disciples entered.

Judas his betrayer also knew the place,

because Jesus had often met there with his disciples.

So Judas got a band of soldiers and guards

from the chief priests and the Pharisees

and went there with lanterns, torches, and weapons.

Jesus, knowing everything that was going to happen to him,

went out and said to them, “Whom are you looking for?”

They answered him, “Jesus the Nazorean.”

He said to them, “I AM.”

Judas his betrayer was also with them.

When he said to them, “I AM, ”

they turned away and fell to the ground.

So he again asked them,

“Whom are you looking for?”

They said, “Jesus the Nazorean.”

Jesus answered,

“I told you that I AM.

So if you are looking for me, let these men go.”

This was to fulfill what he had said,

“I have not lost any of those you gave me.”

Then Simon Peter, who had a sword, drew it,

struck the high priest’s slave, and cut off his right ear.

The slave’s name was Malchus.

Jesus said to Peter,

“Put your sword into its scabbard.

Shall I not drink the cup that the Father gave me?”

So the band of soldiers, the tribune, and the Jewish guards seized Jesus,

bound him, and brought him to Annas first.

He was the father-in-law of Caiaphas,

who was high priest that year.

It was Caiaphas who had counseled the Jews

that it was better that one man should die rather than the people.

Simon Peter and another disciple followed Jesus.

Now the other disciple was known to the high priest,

and he entered the courtyard of the high priest with Jesus.

But Peter stood at the gate outside.

So the other disciple, the acquaintance of the high priest,

went out and spoke to the gatekeeper and brought Peter in.

Then the maid who was the gatekeeper said to Peter,

“You are not one of this man’s disciples, are you?”

He said, “I am not.”

Now the slaves and the guards were standing around a charcoal fire

that they had made, because it was cold,

and were warming themselves.

Peter was also standing there keeping warm.

The high priest questioned Jesus

about his disciples and about his doctrine.

Jesus answered him,

“I have spoken publicly to the world.

I have always taught in a synagogue

or in the temple area where all the Jews gather,

and in secret I have said nothing. Why ask me?

Ask those who heard me what I said to them.

They know what I said.”

When he had said this,

one of the temple guards standing there struck Jesus and said,

“Is this the way you answer the high priest?”

Jesus answered him,

“If I have spoken wrongly, testify to the wrong;

but if I have spoken rightly, why do you strike me?”

Then Annas sent him bound to Caiaphas the high priest.

Now Simon Peter was standing there keeping warm.

And they said to him,

“You are not one of his disciples, are you?”

He denied it and said,

“I am not.”

One of the slaves of the high priest,

a relative of the one whose ear Peter had cut off, said,

“Didn’t I see you in the garden with him?”

Again Peter denied it.

And immediately the cock crowed.

Then they brought Jesus from Caiaphas to the praetorium.

It was morning.

And they themselves did not enter the praetorium,

in order not to be defiled so that they could eat the Passover.

So Pilate came out to them and said,

“What charge do you bring against this man?”

They answered and said to him,

“If he were not a criminal,

we would not have handed him over to you.”

At this, Pilate said to them,

“Take him yourselves, and judge him according to your law.”

The Jews answered him,

“We do not have the right to execute anyone, ”

in order that the word of Jesus might be fulfilled

that he said indicating the kind of death he would die.

So Pilate went back into the praetorium

and summoned Jesus and said to him,

“Are you the King of the Jews?”

Jesus answered,

“Do you say this on your own

or have others told you about me?”

Pilate answered,

“I am not a Jew, am I?

Your own nation and the chief priests handed you over to me.

What have you done?”

Jesus answered,

“My kingdom does not belong to this world.

If my kingdom did belong to this world,

my attendants would be fighting

to keep me from being handed over to the Jews.

But as it is, my kingdom is not here.”

So Pilate said to him,

“Then you are a king?”

Jesus answered,

“You say I am a king.

For this I was born and for this I came into the world,

to testify to the truth.

Everyone who belongs to the truth listens to my voice.”

Pilate said to him, “What is truth?”

When he had said this,

he again went out to the Jews and said to them,

“I find no guilt in him.

But you have a custom that I release one prisoner to you at Passover.

Do you want me to release to you the King of the Jews?”

They cried out again,

“Not this one but Barabbas!”

Now Barabbas was a revolutionary.

Then Pilate took Jesus and had him scourged.

And the soldiers wove a crown out of thorns and placed it on his head,

and clothed him in a purple cloak,

and they came to him and said,

“Hail, King of the Jews!”

And they struck him repeatedly.

Once more Pilate went out and said to them,

“Look, I am bringing him out to you,

so that you may know that I find no guilt in him.”

So Jesus came out,

wearing the crown of thorns and the purple cloak.

And he said to them, “Behold, the man!”

When the chief priests and the guards saw him they cried out,

“Crucify him, crucify him!”

Pilate said to them,

“Take him yourselves and crucify him.

I find no guilt in him.”

The Jews answered,

“We have a law, and according to that law he ought to die,

because he made himself the Son of God.”

Now when Pilate heard this statement,

he became even more afraid,

and went back into the praetorium and said to Jesus,

“Where are you from?”

Jesus did not answer him.

So Pilate said to him,

“Do you not speak to me?

Do you not know that I have power to release you

and I have power to crucify you?”

Jesus answered him,

“You would have no power over me

if it had not been given to you from above.

For this reason the one who handed me over to you

has the greater sin.”

Consequently, Pilate tried to release him; but the Jews cried out,

“If you release him, you are not a Friend of Caesar.

Everyone who makes himself a king opposes Caesar.”

When Pilate heard these words he brought Jesus out

and seated him on the judge’s bench

in the place called Stone Pavement, in Hebrew, Gabbatha.

It was preparation day for Passover, and it was about noon.

And he said to the Jews,

“Behold, your king!”

They cried out,

“Take him away, take him away! Crucify him!”

Pilate said to them,

“Shall I crucify your king?”

The chief priests answered,

“We have no king but Caesar.”

Then he handed him over to them to be crucified.

So they took Jesus, and, carrying the cross himself,

he went out to what is called the Place of the Skull,

in Hebrew, Golgotha.

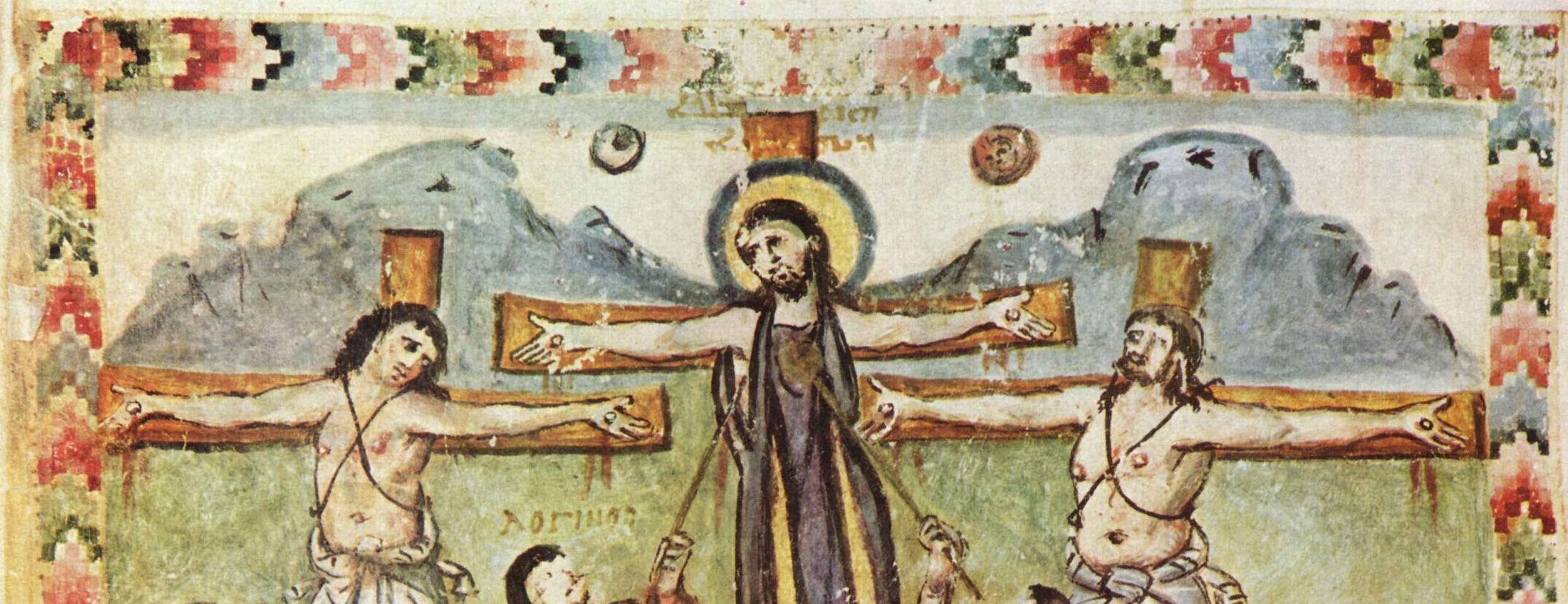

There they crucified him, and with him two others,

one on either side, with Jesus in the middle.

Pilate also had an inscription written and put on the cross.

It read,

“Jesus the Nazorean, the King of the Jews.”

Now many of the Jews read this inscription,

because the place where Jesus was crucified was near the city;

and it was written in Hebrew, Latin, and Greek.

So the chief priests of the Jews said to Pilate,

“Do not write ‘The King of the Jews,’

but that he said, ‘I am the King of the Jews’.”

Pilate answered,

“What I have written, I have written.”

When the soldiers had crucified Jesus,

they took his clothes and divided them into four shares,

a share for each soldier.

They also took his tunic, but the tunic was seamless,

woven in one piece from the top down.

So they said to one another,

“Let’s not tear it, but cast lots for it to see whose it will be, ”

in order that the passage of Scripture might be fulfilled that says:

They divided my garments among them,

and for my vesture they cast lots.

This is what the soldiers did.

Standing by the cross of Jesus were his mother

and his mother’s sister, Mary the wife of Clopas,

and Mary of Magdala.

When Jesus saw his mother and the disciple there whom he loved

he said to his mother, “Woman, behold, your son.”

Then he said to the disciple,

“Behold, your mother.”

And from that hour the disciple took her into his home.

After this, aware that everything was now finished,

in order that the Scripture might be fulfilled,

Jesus said, “I thirst.”

There was a vessel filled with common wine.

So they put a sponge soaked in wine on a sprig of hyssop

and put it up to his mouth.

When Jesus had taken the wine, he said,

“It is finished.”

And bowing his head, he handed over the spirit.

[Here all kneel and pause for a short time.]

Now since it was preparation day,

in order that the bodies might not remain on the cross on the sabbath,

for the sabbath day of that week was a solemn one,

the Jews asked Pilate that their legs be broken

and that they be taken down.

So the soldiers came and broke the legs of the first

and then of the other one who was crucified with Jesus.

But when they came to Jesus and saw that he was already dead,

they did not break his legs,

but one soldier thrust his lance into his side,

and immediately blood and water flowed out.

An eyewitness has testified, and his testimony is true;

he knows that he is speaking the truth,

so that you also may come to believe.

For this happened so that the Scripture passage might be fulfilled:

Not a bone of it will be broken.

And again another passage says:

They will look upon him whom they have pierced.

After this, Joseph of Arimathea,

secretly a disciple of Jesus for fear of the Jews,

asked Pilate if he could remove the body of Jesus.

And Pilate permitted it.

So he came and took his body.

Nicodemus, the one who had first come to him at night,

also came bringing a mixture of myrrh and aloes

weighing about one hundred pounds.

They took the body of Jesus

and bound it with burial cloths along with the spices,

according to the Jewish burial custom.

Now in the place where he had been crucified there was a garden,

and in the garden a new tomb, in which no one had yet been buried.

So they laid Jesus there because of the Jewish preparation day;

for the tomb was close by.

The reading on Good Friday of the passion according to John is a tradition that probably dates back to the earliest centuries of the Church.

John’s passion narrative has a significantly different perspective than that of the synoptic gospels. Unlike the other gospels, John’s passion account has no agony of Jesus in the garden, no kiss of Judas, no flight of the disciples, no trial before the Sanhedrin, no flogging at the high priest’s house or at Herod’s, no mockery by the crowd at the crucifixion, no cry of dereliction from the cross, no darkness covering the land at Jesus’ death, no episode of the good thief, and no story of the death of Judas.

Instead, John’s narrative adds several unique episodes, which will be highlighted throughout the text. What results is John’s particular theological portrait of Jesus. Here he is not a passive victim acted upon by the powers of this world; at every turn, he is the master of his fate. Again and again, his kingship makes itself evident until he is finally lifted up in exaltation on the cross.

Jesus went out with his disciples across the Kidron valley to where there was a garden, into which he and his disciples entered.

Kidron Valley is literally “the winter-flowing Kidron,” a wadi that only has water during the winter rains. Located between Jerusalem and the Mount of Olives, and had fields and gardens adjoining to it, one of which Jesus enters after crossing the valley.

When he was in Jerusalem, Jesus typically retired at the Mount of Olives after a day of public work. He did not change his custom on this day, despite knowing what was about to befall him. He may have also avoided being seized in the city in order to prevent turmoil and/or bloodshed.

Only John’s gospel notes that Jesus entered a garden. He is likely highlighting the theme of Jesus as the new Adam, with his obedience to the Father’s will occurring in a garden, just as Adam’s disobedience had occurred in Eden. This fits with the Genesis imagery woven throughout John’s gospel.

Judas his betrayer also knew the place, because Jesus had often met there with his disciples.

The name Judas is the Greek form of Judah (which in Hebrew means “praised”), a proper name frequently found both in the Old and the New Testament. Even among the Twelve, there were two that bore the name; it is likely for this reason he is specified here as “Judas his betrayer.”

So Judas got a band of soldiers and guards from the chief priests and the Pharisees and went there with lanterns, torches, and weapons.

The Greek word for “a band of soldiers” is spira, a word that describes a military cohort — a group of 600 well-trained Roman soldiers, or more likely, the maniple of 200 under their tribune. Their presence hints at Roman collusion in the action against Jesus before he was even brought to Pilate.

“Guards from the chief priests” is essentially the Jewish police. Representatives of the religious leaders of Israel (the Pharisees) are also with the arresting party. Christ’s friends were few, his enemies many.

The lanterns and torches highlight the fact that this is the hour of darkness.

Jesus, knowing everything that was going to happen to him, went out and said to them, “Whom are you looking for?”

It’s almost shocking that Jesus calmly walks out to greet hundreds of armed soldiers and cordially asks whom they are seeking.

They answered him, “Jesus the Nazorean.” He said to them, “I AM.”

Jesus responds to those who have come for him with a simple self-identification: Ego eimi.

‘I AM’ is the glorious name of the blessed God (Exodus 3:14). This would not have been lost on his accusers.

Judas his betrayer was also with them.

It must have been shocking and infuriating for the apostles to see one of their own with Jesus’ enemies.

When he said to them, “I AM, ” they turned away and fell to the ground.

A display of Jesus’ divine power. These two short, simple words speak them to the ground.

This reveals two important points: 1) clearly Jesus possesses the power to strike them all down if he so chose, and 2) this moment afforded him an opportunity to slip away if he so chose, as he had so many times before.

So he again asked them, “Whom are you looking for?” They said, “Jesus the Nazorean.” Jesus answered, “I told you that I AM. So if you are looking for me, let these men go.”

Jesus moves to protect the disciples from harm, as they could have easily been arrested with him.

Note that he speaks this as a command to them, rather than a request. They are at his mercy, not he at theirs.

This was to fulfill what he had said, “I have not lost any of those you gave me.”

See John 6:39, 10:28, 17:12.

Then Simon Peter, who had a sword, drew it, struck the high priest’s slave, and cut off his right ear. The slave’s name was Malchus.

The slave’s name is noted, for the greater certainty of the account. It’s likely that Peter was aiming for the top of his head and missed, cutting off his ear. His zeal is admirable but misguided.

Jesus said to Peter, “Put your sword into its scabbard. Shall I not drink the cup that the Father gave me?”

Note that Peter’s brash action occurs immediately after Jesus’ appeal to have them set free. Christ has set his intent to do his Father’s will by suffering and dying, an event which he foretold to Peter and the others more than once. Whether he intends to or not, at this point Peter is directly opposing Jesus’ wishes.

Luke’s account tells us Jesus touched the slave’s ear and healed him instantly (Luke 22:50-51).

So the band of soldiers, the tribune, and the Jewish guards seized Jesus, bound him,

Mark’s gospel tells us that at this point, all his disciples deserted him and fled (Mark 14:50).

and brought him to Annas first. He was the father-in-law of Caiaphas, who was high priest that year.

Only John mentions an inquiry before Annas. As we will see, Caiaphas and the Sanhedrin are assembled at Caiaphas’ home, awaiting the prisoner. Why then bring Jesus to Annas?

Commentators speculate that Annas might have been too infirm to attend the council, especially at this late hour. Or perhaps Caiaphas granted him the favor of seeing the prisoner first, especially since they had wanted him arrested for so long.

It was Caiaphas who had counseled the Jews that it was better that one man should die rather than the people.

See John 11:47-53.

Simon Peter and another disciple followed Jesus. Now the other disciple was known to the high priest, and he entered the courtyard of the high priest with Jesus. But Peter stood at the gate outside.

After initially fleeing, Peter and another apostle follow behind as they lead Jesus away. When Peter finds that he cannot enter the courtyard, he stands outside the gate, as close as he can get to Jesus. There is clearly inner turmoil for Peter, who is terrified of what is transpiring, but also wanting to know what becomes of Jesus and desires to fulfill the promises he has made to stand by him.

The identity of the other disciple isn’t clear. Many believe it is Saint John, who often refers to himself in the third person in his gospel and is often linked with Peter. However, it is unclear how he might have been known to the high priest, especially being a Galilaean.

So the other disciple, the acquaintance of the high priest, went out and spoke to the gatekeeper and brought Peter in.

It was quite brave for Peter to come here, especially considering that he had just cut off the ear of the high priest’s servant.

Then the maid who was the gatekeeper said to Peter, “You are not one of this man’s disciples, are you?” He said, “I am not.”

Peter’s first denial of Christ, as foretold by Jesus in John 13:36-38.

Now the slaves and the guards were standing around a charcoal fire that they had made, because it was cold, and were warming themselves. Peter was also standing there keeping warm.

The weather was cold, for it was early springtime and it was now after midnight. Peter does his best to blend in with the slaves and guards in the courtyard.

The high priest questioned Jesus about his disciples and about his doctrine.

He is seeking information that would implicate Jesus in a crime, such as gathering followers for a revolt against Rome (his disciples) or blasphemy (his doctrine).

Jesus answered him, “I have spoken publicly to the world. I have always taught in a synagogue or in the temple area where all the Jews gather, and in secret I have said nothing. Why ask me? Ask those who heard me what I said to them. They know what I said.”

In John’s gospel, Jesus is not silent during his two trials but engages in dialogue with Annas and with Pilate.

Jesus taught in the open to great crowds, speaking plainly. There has been nothing secretive about his ministry. Further, Jesus is the defendant, and yet is being asked to provide evidence against himself.

When he had said this, one of the temple guards standing there struck Jesus and said, “Is this the way you answer the high priest?” Jesus answered him, “If I have spoken wrongly, testify to the wrong; but if I have spoken rightly, why do you strike me?”

If they had any evidence that Jesus’ teachings were blasphemous, they should submit that evidence. If his teachings were not blasphemous, he did not deserve this kind of treatment.

Then Annas sent him bound to Caiaphas the high priest. Now Simon Peter was standing there keeping warm. And they said to him, “You are not one of his disciples, are you?” He denied it and said, “I am not.”

Peter’s second denial.

One of the slaves of the high priest, a relative of the one whose ear Peter had cut off, said, “Didn’t I see you in the garden with him?” Again Peter denied it. And immediately the cock crowed.

Peter’s third denial. The synoptic gospels tell us that Peter immediately remembered Jesus’ prediction, and broke down and wept.

Then they brought Jesus from Caiaphas to the praetorium.

The praetorium was the official residence and military headquarters of a Roman governor, where he had his guard and held court.

It was morning.

Jewish custom forbade night trials, with serious charges. Since such trials had no legal validity, the Sanhedrin waits until morning to take further action.

And they themselves did not enter the praetorium, in order not to be defiled so that they could eat the Passover.

The homes of Gentiles (idolaters) were considered unclean.

So Pilate came out to them and said, “What charge do you bring against this man?”

Pontius Pilate was governor of Judea at this time, the ranking Roman official of the land. The Jewish leaders brought Jesus before him because, being under Roman law, they could not carry out capital punishment on their own. They were seeking a public sentence of death to counteract Jesus’ reputation and erase his teaching from the people’s minds.

They answered and said to him, “If he were not a criminal, we would not have handed him over to you.” At this, Pilate said to them, “Take him yourselves, and judge him according to your law.” The Jews answered him, “We do not have the right to execute anyone,”

The Jewish leaders insinuate that Jesus was guilty of a serious crime, a crime recognizable by Caesar’s court.

in order that the word of Jesus might be fulfilled that he said indicating the kind of death he would die.

While Jesus was going up to Jerusalem, he took the twelve disciples aside by themselves, and said to them on the way, “See, we are going up to Jerusalem, and the Son of Man will be handed over to the chief priests and scribes, and they will condemn him to death; then they will hand him over to the Gentiles to be mocked and flogged and crucified; and on the third day he will be raised” (Matthew 20:19)

So Pilate went back into the praetorium and summoned Jesus and said to him, “Are you the King of the Jews?”

The title of king will play a pivotal role throughout this scene and is the center of the interaction with Pilate.

It is unclear whether Pilate had previously heard that Jesus and/or his followers had claimed royalty, or whether the Jews had suggested to Pilate was his crime. Based on Jesus’ admission to the high priest that he was the Messiah, it is likely the latter.

Regardless, the question obviously affected the position of Caesar, which is Pilate’s focus and priority.

Jesus answered, “Do you say this on your own or have others told you about me?”

Jesus is pointing out the obvious. Jesus had never done anything to arouse Pilate’s suspicions: he never assumed any secular power, never portrayed himself as a threat, never acted as a judge or insurrectionist, never said anything traitorous.

That being the case, others must have told him about Jesus. The implication here is that, as a judge, Pilate should be suspicious of the motives of anyone who would try to manipulate him into using his power as governor.

Pilate answered, “I am not a Jew, am I? Your own nation and the chief priests handed you over to me. What have you done?”

Pilate misses the nuances of Jesus’ words; he presses on.

Jesus answered, “My kingdom does not belong to this world. If my kingdom did belong to this world, my attendants would be fighting to keep me from being handed over to the Jews. But as it is, my kingdom is not here.” So Pilate said to him, “Then you are a king?”

Pilate was very keen to suss out the matter of Jesus’ claims to kingship; any negligence on his part in an affair like this would carry a heavy punishment from Rome.

Jesus answered, “You say I am a king. For this I was born and for this I came into the world, to testify to the truth. Everyone who belongs to the truth listens to my voice.”

The purpose of Christ’s miraculous birth, and of his entire life on earth, was to bear testimony to truth.

Pilate said to him, “What is truth?”

The irony here is that truth is literally standing before him: Jesus Christ himself is truth. He is true God, and true man.

When he had said this, he again went out to the Jews and said to them, “I find no guilt in him.

Pilate is used to dealing with rebels and realizes that Jesus is no serious threat to the Roman Empire.

But you have a custom that I release one prisoner to you at Passover. Do you want me to release to you the King of the Jews?”

The custom of releasing a prisoner at Passover is not attested to outside the gospels.

They cried out again, “Not this one but Barabbas!” Now Barabbas was a revolutionary.

Barabbas is a notorious insurrectionist. There is much symbolism in this choice, because the name Barabbas means “son of the father.” In choosing him, the crowds favor this false “son of the father,” who represents violence and vengence, over Jesus, The Son of The Father, who represents peace and forgiveness.

Then Pilate took Jesus and had him scourged.

Roman scourging was much more severe than a whipping. It normally involved the prisoner’s being stripped and tied to a pillar or low post. The whip had multi-stranded leather thongs ending with sharp pieces of bone or metal spikes, which would rip a person’s flesh in a single stroke. Prisoners often died from this punishment.

And the soldiers wove a crown out of thorns and placed it on his head, and clothed him in a purple cloak,

A costume of cruel sarcasm, mocking his claim to kingship.

and they came to him and said, “Hail, King of the Jews!” And they struck him repeatedly.

This scene represents the height of Jesus’ humiliation. The crude sport of the soldiers expresses their contempt not only for the alleged king but also for the people whose king this was purported to be. They even mimic the royal address one would give to the emperor (“Hail, Caesar!”).

While they scoff at Jesus, they have no idea how appropriate their words actually are. Despite their cruel intentions, they unwittingly proclaim the truth of Jesus Christ: He really is the Messiah, the true King of the Jews. The homage these pagan soldiers pay in jest anticipates the sincere honor countless Christians will give Jesus as they worship him as their Lord and King.

Once more Pilate went out and said to them, “Look, I am bringing him out to you, so that you may know that I find no guilt in him.” So Jesus came out, wearing the crown of thorns and the purple cloak. And he said to them, “Behold, the man!”

Pilate presents Jesus to the Jewish leaders, repeating his assertion of innocence, in hopes that they would now be satisfied and drop the matter.

When the chief priests and the guards saw him they cried out, “Crucify him, crucify him!”

Crucifixion was an Oriental method of punishment adopted by the Romans, usually reserved only for slaves, bandits, and rebels. It was prohibited by Roman law to crucify Roman citizens.

Crucifixion was a slow and agonizing death. Nails were probably driven through the wrists rather than the palms. The weight of the suspended body made breathing difficult and painful. Involuntary efforts by the legs to ease the pressure greatly increased pain in the feet, an ordeal that continued until the exhausted victim could no longer breathe. In some cases, this might take several days, which is why prisoners were sometimes weakened by first flogging or scourging them.

Pilate said to them, “Take him yourselves and crucify him. I find no guilt in him.”

Again he states Jesus’ innocence.

The Jews answered, “We have a law, and according to that law he ought to die, because he made himself the Son of God.”

Realizing that Pilate could not be moved against Jesus by alleging that he claimed to be a king, the Jewish leaders up the ante. Referencing the law of Moses, they add the charge of Jesus claiming to be a god.

Now when Pilate heard this statement, he became even more afraid,

Recall that the Roman emperor was believed to have divine status. If Jesus is divine, he is all the more threat to Caesar.

and went back into the praetorium and said to Jesus, “Where are you from?” Jesus did not answer him.

Jesus wasn’t silent for lack of things to say. If he were seeking to save his own life, now would be the time to speak, but he had determined to lay down his life. He is patiently submitting to the Father’s will.

He was oppressed, and he was afflicted, yet he did not open his mouth; like a lamb that is led to the slaughter, and like a sheep that before its shearers is silent, so he did not open his mouth (Isaiah 53:7).

So Pilate said to him, “Do you not speak to me? Do you not know that I have power to release you and I have power to crucify you?”

In stark contrast to Jesus’ silence, Pilate boasts of his authority.

Jesus answered him, “You would have no power over me if it had not been given to you from above.

Jesus rebukes Pilate’s arrogance. While Pilate’s religious beliefs obviously differ from the Jews, it would have nevertheless reminded him that his power was both limited and also provided to him by the divine emporer.

For this reason the one who handed me over to you has the greater sin.”

Jesus questions Pilate’s righteousness as a judge. He has failed to consider the motives of those who handed Jesus over to him.

Consequently, Pilate tried to release him; but the Jews cried out, “If you release him, you are not a Friend of Caesar. Everyone who makes himself a king opposes Caesar.”

“Friend of Caesar” is a Roman honorific title bestowed upon high-ranking officials for merit.

Pilate seems more determined than ever to have Jesus released, but the Jewish leaders escalate by openly questioning his loyalty to Rome. There is an implied threat here to inform against Pilate and have him displaced, as governors frequently were.

When Pilate heard these words he brought Jesus out and seated him on the judge’s bench

Others translate this as Pilate being the one who sat on the judge’s bench. If Jesus is the one who sat, then John would be highlighting the fact that Jesus is the true judge of the entire world; if Pilate is who sat, it would reflect the fact that he has suddenly yielded to the Jewish leaders and has taken his place to finish the trial.

in the place called Stone Pavement, in Hebrew, Gabbatha. It was preparation day for Passover, and it was about noon.

The evangelist takes note of the precise place and time of Jesus’ condemnation. Noon was the hour which the priests began to slaughter Passover lambs in the Temple; this is likely an intentional connection by the gospel writer.

And he said to the Jews, “Behold, your king!” They cried out, “Take him away, take him away! Crucify him!” Pilate said to them, “Shall I crucify your king?” The chief priests answered, “We have no king but Caesar.” Then he handed him over to them to be crucified.

Whereas the earlier questioning was informal in nature, this seems to be the official proceedings.

If Pilate found no guilt in him, as he said, he should have released Jesus immediately. Rather than take a stand to protect the innocent, he cowardly caves to the pressure and allows Jesus to be scourged and crucified.

So they took Jesus, and, carrying the cross himself, he went out

Roman crucifixions generally took place outside the city walls along crowded roads so that many people could see what happened when someone revolted against Rome. At the crucifixion site, the vertical part of the cross was planted in the ground. The condemned criminal was given the crossbeam in the city and had it placed over his shoulders like a yoke, with his arms hooked over it. He would be forced to carry the crossbeam through the streets and out the city gates.

The picture of Jesus carrying the cross himself is a departure from the synoptic accounts, especially in Luke (23:26) where Simon of Cyrene is made to carry the cross, walking behind Jesus. In John’s theology, Jesus remained in complete control and master of his destiny.

to what is called the Place of the Skull, in Hebrew, Golgotha.

The name Calvary comes into English from the Rheims New Testament translation of the Latin calvariae. Hebrew (and Christian) legend has it that Adam’s skull was buried there (hence the depiction of a skull beneath the cross in some crucifixion paintings). The second Adam is sacrificed over the remains of the first.

There they crucified him, and with him two others, one on either side, with Jesus in the middle.

All four Gospels state that Jesus was crucified between two criminals; in his death, he “was numbered with the transgressors” (Isaiah 53:12).

The goal of crucifixion was not simply to execute but to do so with the maximum amount of pain and public humiliation. Stripped of clothing and nailed or bound to a cross with their arms extended and raised, their exposed bodies had no means of coping with heat, cold, insects, or pain.

Pilate also had an inscription written and put on the cross. It read, “Jesus the Nazorean, the King of the Jews.”

The inscription differs slightly in each gospel account. John’s form is the fullest and gives the equivalent of the Latin INRI = Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum.

Now many of the Jews read this inscription, because the place where Jesus was crucified was near the city; and it was written in Hebrew, Latin, and Greek.

Only John mentions the polyglot character of the inscription, as well as Pilate’s role in keeping the title unchanged, which follows.

So the chief priests of the Jews said to Pilate, “Do not write ‘The King of the Jews,’ but that he said, ‘I am the King of the Jews.’” Pilate answered, “What I have written, I have written.”

The placard at the head of the cross specified the crime. Pilate was insulting the Jewish leaders, but the irony of its truth would have been very apparent to the early church. John is highlighting Jesus’ kingship.

When the soldiers had crucified Jesus, they took his clothes and divided them into four shares, a share for each soldier. They also took his tunic, but the tunic was seamless, woven in one piece from the top down. So they said to one another, “Let’s not tear it, but cast lots for it to see whose it will be,” in order that the passage of Scripture might be fulfilled that says: They divided my garments among them, and for my vesture they cast lots. This is what the soldiers did.

The division of garments was a privilege of the squad of soldiers who handled the execution; the crucified were stripped entirely nude as a final humiliation.

This action fulfilled Psalm 22:18, as John explicitly points out. In fact, the events surrounding the crucifixion of Jesus include numerous fulfillments of Psalm 22. John is again demonstrating that Jesus is in full control, willfully submitting to his suffering and death.

Standing by the cross of Jesus were his mother and his mother’s sister, Mary the wife of Clopas, and Mary of Magdala.

Standing by the cross, as near as they can get, are the Blessed Mother, along with a handful of friends and relatives. They cannot rescue him or relieve any of his sufferings; nevertheless, they are simply present.

We can only imagine the pain it gave the Blessed Mother to see her son in this state. Simeon’s prophecy has been fulfilled: A sword shall pierce through your own soul (Luke 2:35).

When Jesus saw his mother and the disciple there whom he loved

John refers to himself as “the disciple whom Jesus loved.” All the other disciples have fled.

he said to his mother, “Woman, behold, your son.” Then he said to the disciple, “Behold, your mother.” And from that hour the disciple took her into his home.

Joseph had died long before; in Jewish society, widows with no male relative were often destitute. A woman who has lost her male agency in a patriarchal society was powerless.

Therefore, even in his great suffering, Jesus ministers to others, tenderly providing for his mother at his death. He asks his mother to look upon John as her son, and for John to care for Mary as his own mother.

After this, aware that everything was now finished, in order that the Scripture might be fulfilled, Jesus said, “I thirst.”

Psalms 22:15 foretold his tremendous thirst: my mouth is dried up like a potsherd, and my tongue sticks to my jaws.

There was a vessel filled with common wine. So they put a sponge soaked in wine on a sprig of hyssop and put it up to his mouth.

Most translations say “sour wine” or “vinegar.” Psalms 69:22 is fulfilled: they gave me vinegar to drink for my thirst.

John does not mention the drugged wine, a narcotic that Jesus refused as the crucifixion began (Mark 15:23), but only this final gesture of kindness at the end (Mark 15:36). It is sour wine, the ordinary drink of the soldiers, called posen.

Hyssop is a small plant and hardly able to hold the weight of a sponge filled with wine. It may be a symbolic reference to the hyssop that was used to sprinkle the blood on the doorposts and lintel in the first Passover (Exodus 12:22).

When Jesus had taken the wine, he said, “It is finished.”

What was finished? Not the wine, but the entire will of the Father:

- the Father’s will that he should take on human flesh, be exposed to shame and reproach, suffer greatly, and die,

- the work his Father gave him to do, to preach the Gospel, work miracles, and obtain eternal salvation for his people,

- fulfillment of the prophets, and

- fulfillment of the law (giving perfect obedience to it and enduring the penalty of death), securing redemption from its curse and atoning fully for all sin.

And bowing his head, he handed over the spirit.

Note how John, by his phrasing, continually portrays Jesus as being in control. He chooses to bow his head, and actively hands over the spirit. He is emphasizing that above all else, Jesus is freely submitting to the Father’s will.

“He handed over the spirit” carries a double meaning: he gave his last breath and also passed on the Holy Spirit (see John 7:39).

Now since it was preparation day, in order that the bodies might not remain on the cross on the sabbath, for the sabbath day of that week was a solemn one, the Jews asked Pilate that their legs be broken and that they be taken down.

The sabbath commenced on Friday evening at six o’clock. According to the sabbath laws, the work of burying Jesus must be completed before that time. The legs of the crucified were broken in order to hasten death, when necessary.

So the soldiers came and broke the legs of the first and then of the other one who was crucified with Jesus. But when they came to Jesus and saw that he was already dead, they did not break his legs, but one soldier thrust his lance into his side, and immediately blood and water flowed out.

Some commentators believe that John is emphasizing the reality of Jesus’ death as a way to speak against the docetic heretics, who believed that Christ did not have a real or natural body during his life on earth, but only the illusion of one.

The mixture of blood and water was likely the result of the pericardium being pierced by the lance. This is a membrane around the heart that, given the trauma Jesus has endured, has filled with fluid. In the blood and water, many see a reference to the Eucharist and baptism.

An eyewitness has testified, and his testimony is true; he knows that he is speaking the truth, so that you also may come to believe.

John is referring to his own eyewitness account, recorded here in his gospel for the benefit of all who would receive it.

For this happened so that the Scripture passage might be fulfilled: Not a bone of it will be broken.

Psalms 34:20: He keeps all their bones; not one of them will be broken.

Exodus 12:46: [The Passover lamb] shall be eaten in one house; you shall not take any of the animal outside the house, and you shall not break any of its bones.

And again another passage says: They will look upon him whom they have pierced.

Zechariah 12:10.

After this, Joseph of Arimathea, secretly a disciple of Jesus for fear of the Jews, asked Pilate if he could remove the body of Jesus. And Pilate permitted it. So he came and took his body.

Mark and Luke identify Joseph as a member of the Sanhedrin. John and Matthew may have seen a problem in the discipleship of a member of the council that had voted the death of Jesus, but it is unclear whether Joseph actually attended the council meeting. Arimathea is about twenty miles northeast of Jerusalem.

Nicodemus, the one who had first come to him at night,

John 3:1-21.

also came bringing a mixture of myrrh and aloes weighing about one hundred pounds.

This was a very large and costly quantity of precious spices.

They took the body of Jesus and bound it with burial cloths along with the spices, according to the Jewish burial custom.

The custom was to wrap the body in linen, rolling the cloth around it many times.

Now in the place where he had been crucified there was a garden, and in the garden a new tomb, in which no one had yet been buried. So they laid Jesus there because of the Jewish preparation day; for the tomb was close by.

Matthew’s gospel specifies that the tomb belonged to Joseph of Arimathea. His gift of a tomb completes Jesus’ fulfillment of Isaiah 53:9.

Pilate has met his obligation: the threat to Roman peace and stability has been removed. A contingent from the Jewish ruling body has also accomplished its goals: the contentious wonder-working preacher has been silenced, and any possibility of future upheaval has been sealed in the tomb with his body. Neither Pilate nor the Jewish leaders realize that in reality, everything is now in place for the eschatological event of the resurrection — they have ironically become agents through whom the plan of God unfolds.

Through John’s eyes, Jesus’ submission to his suffering and death is so fully aligned with the Father’s will that already glory and vindication shine through. The way of the cross takes on the trappings of a triumphal procession; a public execution becomes and forum proclaiming God’s judgment and vindication; the cross becomes Jesus’ throne of glory.

John’s passion account is not so much about the cross as it is about the cross transformed into a sign of salvation. Against the background of Preparation Day for Passover, as John intimates, the crucified Jesus is the Passover sacrifice, the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world. In him, the Jewish feast of Passover is transformed once and for all.

Connections and Themes

The prophetic suffering servant. Like the paschal lamb that was sacrificed on behalf of the people, the Suffering Servant of the Lord allows himself to be handed over to the slaughter. Though innocent, he takes upon himself the guilt of the very ones victimizing him. We marvel at the willingness of those who place themselves at risk in order to save anyone who is vulnerable or anyone they love, but to do so for one’s own torturers is beyond human comprehension. Yet that is what Christ our Passover has done. He is the true Suffering Servant; he is the one who has allowed himself to be taken, to be afflicted, to be offered a sacrifice for others. It is his blood that spares us; it is his life that is offered. Through his suffering, this servant justifies many. He is our true Passover.

The great high priest. Jesus is not only the innocent victim, he is also the high priest who offers the Passover sacrifice. Because he is one of us, he carries many of our own weaknesses. But it is because he is without moral blemish that, in him, we all stand before God. On this solemn day, we behold his battered body, but we also look beyond it to the dignity that is his as high priest. Garbed as he is in wounds that rival the ornate garments of liturgical celebration, he offers himself on the altar of the cross. He is our true Passover.

Triumphant king. “King of the Jews” was the crime for which he was tried, sentenced, and executed. It was the title inscribed above his bloody throne. To those passing by, he appeared to be a criminal, but he was indeed a king. His crucifixion was his enthronement. Lifted up on the cross, he was lifted up in triumph and exaltation. He was not a conquered king, he was a conquering king. He willingly faced death and stared it down. As he delivered over his spirit, death lay vanquished at the foot of the cross. Within a few days, this reality would be clear to others. He is our true Passover.

The power of the cross. On Good Friday, the cross gathers together all three images of Christ. It is in the light of this cross that we see clearly how all three must be accepted at once, for we never contemplate one image without contemplating the others. In the midst of the passion, we see the victory; when we celebrate Easter, we do not forget the cross. As we venerate this cross, we gather together the memory of all the living and the dead. With our petitions, we bring to the cross all the needs of the world. In this way, the cross becomes the true axis mundi, the center of the universe, and Christ is revealed as the true Passover.